- Home

- Colette Dartford

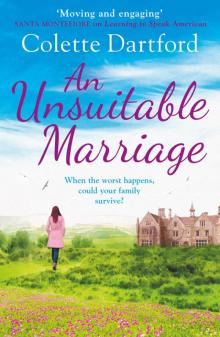

An Unsuitable Marriage

An Unsuitable Marriage Read online

An Unsuitable

Marriage

Colette Dartford

Contents

Prologue

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

An Exclusive Chapter from Learning to Speak American

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

For my husband, Trevor, and our children, Charlotte, Matthew and Nicholas

Prologue

It was Olivia who found the boy. She only went to the changing room because she thought that was where she had dropped her keys, and there he was, suspended from a coat hook, a black leather belt round his neck. At that moment she knew why people claimed not to believe their eyes. It seemed an odd expression, implying one’s eyes had the capacity for deceit, but now she understood it completely.

His face was ashen – a greyish sort of white – his lips tinged with blue. Olivia clamped her hand over her mouth to stifle a cry. She wanted to call the boy’s name but was too shocked to remember it. Instead she lunged forward, grabbed his legs in a kind of bear hug and took the weight of his body in her arms. The obvious thing was to shout for help, but the changing rooms were out of bounds after supper so nobody would hear. She released her right arm, taking all his weight in the left, reached up to the metal buckle and pulled it undone with a hard tug. The boy slumped forward over her shoulder. Freddie Burton. Of course.

Olivia laid him on the bench that ran under the row of hooks and felt his vividly bruised neck for a pulse. New houseparents had to take a first aid course, otherwise she wouldn’t have known that the carotid pulse can be felt on either side of the windpipe, just below the jaw. It was weak and faint, barely there.

‘Freddie,’ she said, her voice artificially calm. ‘Freddie, it’s Mrs Parry. You’re going to be fine.’

She didn’t know if that was true but it seemed the right thing to say. As gently as she could, she manoeuvred him into a sitting position and from there managed to roll him over her shoulder. His build was as stocky as hers was slight, and he felt awkward and heavy as she carried him, fireman-like, along the dimly lit corridor and out into the deserted quad. His bony shoulder pressed painfully into hers. She breathed through the pain, the way she had when Edward was born.

A biting wind whipped fallen leaves into a frenzy. Its ghostly howls drowned Olivia’s pleas for help and she braced herself to scream. From the pit of her stomach she released a shrill, desperate sound, bringing Leo Sheridan, Freddie and Edward’s housemaster, to the dorm-room window. He flung it open and shouted down to her.

‘Olivia? What’s going on?’

‘Ambulance. Call an ambulance.’

Seconds later Leo was in the quad, dashing towards her. Explanations could wait. He relieved her of the boy and carried him into the school building, up the wide stone staircase and past the girls’ dorm to sickbay, where Matron was waiting, her face slack with shock.

‘I’ve called the ambulance and Martin’s on his way,’ she said, helping Leo lay the boy down on a narrow metal-framed bed. Olivia hated the sickbay beds. They had something of a mental asylum about them: austere, cold, frighteningly functional.

Matron checked the boy’s pulse and respiration while Olivia recounted how she had found him, but then Martin Rutherford, the headmaster, rushed in, panting as if he had run from his house at the end of the long driveway, and she had to repeat it all again. He put his hands to his forehead, almost covering his eyes, and shook his head.

‘I don’t understand.’

Olivia summarised. ‘He tried to hang himself.’

‘Good heavens,’ gasped Martin. ‘Is he going to be all right?’

‘He’s breathing,’ said Matron, ‘and there’s a faint pulse. The ambulance will be here soon.’

Martin’s sickly pallor was now strikingly similar to Freddie’s. ‘I should call his parents,’ he said. ‘Burton, isn’t it?’

‘Yes,’ said Leo. ‘He’s in my dorm. The parents are divorced so there are two numbers.’

Martin ran a hand through his thinning hair and pulled himself up into headmaster mode. ‘Fetch those numbers, would you, please,’ he said. ‘And don’t say anything to the other boys yet. This needs to be handled sensitively.’

Olivia didn’t envy Martin the task of breaking the news to Freddie’s parents, a thought interrupted by the piercing scream of approaching sirens, and then everything happened very quickly. Two paramedics checked Freddie’s vital signs, put a collar round his neck and whisked him off to hospital with Matron by his side. Martin and Olivia watched in silence as the ambulance sped away, its flashing blue lights fading into the inclement night.

*

In the tense weeks that followed, an ominous cloud of rumour and disquiet descended on St Bede’s. The press relished an opportunity to engage in a bit of finger-wagging, vilifying those callous parents who ‘farmed out’ the care of their offspring to expensive boarding schools. They dragged up cases where deviant adults had sought out such establishments in order to gain access to vulnerable children. Martin attributed these articles to resentment about perceived privilege and elitism, but it didn’t help that Freddie’s father, Toby Burton, gave an interview citing the school’s ‘near fatal neglect of his son’s welfare’.

It was Freddie who set the record straight. He had lingered in a coma for five agonising days before the prayers offered up at morning chapel were finally answered. He explained that he had hung himself from a coat hook as an early Halloween stunt, his sole intention being to ‘scare the shit’ out of his friends. Freddie was well known as an attention seeker, a serial prankster, but even for him this seemed extreme. Didn’t he realise how dangerous it was, that he could have died? This, Martin confided to Olivia, is what he had asked when visiting Freddie in hospital, but the boy had shrugged and blamed it all on his friends. They were supposed to meet him in the dark and spooky changing room after supper, where they would have found him pretending to be hanged. He had stressed that, Martin said, because he was fed up with being asked stupid questions about whether he meant to harm himself. Olivia was surprised when Martin said that Freddie blamed Edward in particular, because he was the one who had piped up that Doctor Who was about to start, prompting Freddie’s friends to forget him altogether.

‘Let’s hope he never does anything like that again,’ said Olivia, to which Martin replied, ‘Amen.’

It was a relief when October half-term arrived and at chapel, on the last day of school, Martin urged staff and pupils to pray for a return to normality. They had just stood for a hymn – three rousing verses of ‘Give Me Joy in My Heart’ – when the strangest sensation of dread crept over Olivia. Not a premonition as such, but an inexplicable sense of foreboding. At least that’s what she claimed later, although she had no more inkling than anyone else that before the year was over, another boy would be discovered close to death, and this time she would know his name.

One

The prospect of ten days at the Rectory was about to test Olivia’s resolve to make the best of a bad situation. As she packed her bag – a suede Gucci holdall that reminded her of more affluent times – she tried to focus on all the things she would do with Edward, on long country walks with the dogs, on having Geoffrey’s warm body next to her in bed. Sleeping alone was one of the many changes she had been forced to make when she swapped the luxury of

a listed farmhouse for a cramped little flat above the science block at St Bede’s. She shook that thought from her head. No, she refused to dwell on it now.

Edward arrived as she zipped up the holdall. He had Geoffrey’s strong jaw and broad shoulders, her mop of unruly blonde hair. He ran his hand over the top of his head, flattening the curls as best he could, but they sprang back, thick and determined.

‘You ready, Mum?’

No, not really, but until this whole mess was sorted out they had to spend school holidays in the guest room at the Rectory, Edward in Geoffrey’s childhood bedroom, Rowena smug with the pyrrhic victory of having got her precious son back home. Olivia stopped herself right there. No unkind thoughts about Rowena. The pair of them proved the cliché that mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law harboured thinly concealed resentment towards each other, but whatever their history, Rowena was recently widowed and for that, Olivia was genuinely sorry.

Wine would help. She hoped Geoffrey had remembered to buy some. Nothing decent of course – that would be extravagant under the circumstances. Cheap supermarket plonk would be fine.

She glanced round her unlikely refuge and threw Edward a reassuring smile.‘I’m ready.’

*

It had been six weeks since Olivia left Compton Cross in the shimmering heat of an Indian summer, Geoffrey at the wheel of her Land Rover, the boot crammed with bags and boxes. They hadn’t talked much. What was there to say? He was driving her away from the life they had built together but which he had single-handedly dismantled. When he reminded her she had a choice, that it wasn’t too late to change her mind, she had looked out of the window because she didn’t want to look at him.

What were her choices, exactly? Live at the Rectory with Geoffrey and his mother or take a job as houseparent at St Bede’s. Their own house – Manor Farm, their home – was about to be repossessed by the bank. Tucked away at St Bede’s, she would at least be spared the shameful spectacle of their belongings being packed up and driven off to the self-storage unit Geoffrey had rented on the Mendip Industrial Estate. Downings Factory was on the estate too. How was that for irony? He must have read her mood because he had stopped talking and turned on the car radio.

Edward did the same now – found a radio station playing a Coldplay song that reminded Olivia of boozy nights with Johnny and Lorna, the sort that leave you with a pounding headache and queasy stomach. In the morning you wish you hadn’t drunk so much but as the day wears on and the hangover wears off, you remember how much you laughed, how free you felt. Was their friendship spoiled too? She drove past the row of thatched cottages where Johnny and Lorna lived, the twins’ bikes in the front garden, lights on inside even though it was early afternoon. She would call Lorna tomorrow. Definitely.

The lane was thick with tractor mud that splattered the Land Rover in sticky clumps. Countryside and clean cars didn’t go together. Over the summer Edward and the twins went from house to house offering to wash cars for five pounds a time. They didn’t make much money.

‘You OK, Mum?’ he said.

Olivia realised she was frowning and forced a smile. ‘Uh huh.’

‘You’re quiet.’

‘Is that a bad thing?’

He curled the corner of his mouth into a half-smile, exactly like Geoffrey did. Was it a mannerism Edward copied or something imprinted in his DNA? Usually she pined for him during term-time, the house so empty and still without him. The silver lining to her houseparent storm cloud was that she saw Edward all the time at school. It wasn’t the same, though – she had to learn a whole new set of rules. He called her Mrs Parry, pretended he hadn’t seen her if he was with his friends, recoiled in horror if she went to touch him.

One night she committed the heinous crime of wandering along to his dorm to say goodnight. He was sitting in front of the television with the other boarders, the buzz of easy banter all around them, when Freddie Burton spotted her loitering in the doorway and announced in a loud, theatrical voice, ‘Your mummy’s here, Parry.’ Edward turned round, his face crimson with shame, and glared at her. She knew instantly she had transgressed. ‘Doesn’t matter,’ she said quickly and retreated to sounds of mocking and laughter. Not a mistake she would repeat. When she saw him in chapel the next morning they didn’t acknowledge each other. She sat four rows behind him, the back of his head as familiar to her as breathing, everything else disturbingly different. The melancholy hymn didn’t help. ‘In Christ Alone’ – Martin Rutherford’s idea of being modern. Ten minutes later, as they all filed out, Edward offered a conciliatory smile. Nothing obvious, but enough to know she had been forgiven.

She glanced at him in the passenger seat, so smart in his burgundy blazer, white shirt and black trousers. His profile was changing, becoming less soft and childlike, more angular and adolescent. He caught her staring and said, ‘You seem a bit weird.’

She raised her eyebrows. ‘Only a bit?’ She turned it back on him. ‘Are you OK, darling?’

He bobbed his head, more to the beat of the music than in response to her question. She had thought the thirty-minute drive would be a good opportunity for them to talk but he seemed happy and relaxed and she didn’t want to spoil that.

A city girl born and bred, Olivia had been wary of moving to Compton Cross. So much grass, so few people. She drove slowly through the narrow lane that skirted the village green, recognised the scatter of vehicles parked outside the Lamb and Lion, waved to a fellow dog walker whose name she could never remember and then turned into the Rectory. The gate was open, Geoffrey’s silver Mercedes in the driveway, its personalised plate a source of chronic embarrassment: GP 007. Olivia complained it was crass – you’re not a doctor or a secret agent, you own a factory – but he pointed out they were his initials and anyway, it was a collector’s item: a good investment. He never told her how much the coveted number plate had set him back, no matter how many times she asked.

She turned off the engine and sat for a moment. Edward undid his seat belt and looked at her, waiting. Was he really that resilient? He had lost his home too.

Geoffrey opened the front door and Edward jumped out to greet him. Their manly hug was a pleasure to watch – lots of back-slapping and that boxing thing where they pretended to spar with each other. When Geoffrey looked in Olivia’s direction he offered a faux frown and tilted his head to one side. Thirteen years together – she could read him so well. His look said: sorry about all this shit, I know I’ve screwed up, please be nice. She got out of the car and walked over to him as Rollo and Dice bounded out of the house, tails wagging, wild with excitement. They leaped up at Edward, lashing his face with their rough pink tongues. A cacophony of barking accompanied the reunion: a picture of innocence and joy that eased Olivia’s trepidation about the days ahead.

‘It’ll be fine,’ said Geoffrey, reading her mind. ‘I promise.’

*

Don’t make promises you can’t keep.

Geoffrey showed Olivia to their room, its musty odour clinging to them like a damp shroud, and put her holdall on the bed.

She thought he might make a lame joke – tell her not to get too excited, or ‘it’s not exactly the Ritz, is it?’ – but he didn’t. All he said was that his mother had made lunch and she could unpack later.

Olivia followed him to the kitchen – large, old-fashioned, redeemed by the warmth of a bottle-green Aga – where Edward was already sitting at the long pine table, chomping on an apple, the dogs curled obediently at his feet. Rowena, busy slicing a loaf of home-made bread, put down the knife and wiped her hands on her apron.

‘There you are,’ she said. ‘I was expecting you earlier.’

The first subtle barb of the day. By implication Olivia was late, even though she had said she would arrive around two and it was ten minutes past. In her head she heard Geoffrey tell her not to be so sensitive, that it was a perfectly innocent comment and his mother didn’t mean anything by it, but Olivia felt that she absolutely did.

They took

a few steps towards each other until they were close enough to peck cheeks. Rowena’s signature scent – dough, Jeyes fluid, a hint of lavender soap – stirred a deep-seated sense of grievance. Olivia had been judged and found wanting and however many years had passed, Geoffrey could not persuade her that was then and this is now. Get over it, move on, were his stock pleas when she complained about his mother’s slights. Did he genuinely not see them, or did he choose not to see them? Or maybe he was right and Olivia took offence where none existed.

Rowena looked the same as she always did: tallish and straight-backed, weathered face, devoid of creams or cosmetics, steel-grey hair pinned into a loose low bun. She wore a long woollen cardigan over a blouse, buttoned to her throat, and a calf-length pleated skirt. There was no outward sign that just three months ago she had lost her husband of forty-five years, but she must surely be in pain. Olivia resolved again to make a special effort, although it wouldn’t be easy. Two women under one roof? They had both run their own homes, managed their own families, lived separate but intersecting lives until Geoffrey’s financial problems changed everything. Homelessness had imposed a sense of humiliation that unbalanced the scales in Rowena’s favour. Olivia was unsure of her status, her role. Should she treat the Rectory as her home, come and go as she pleased, have a long lie-in if she felt like it, invite friends over for coffee and a chat? Or would she fall foul of the tacit set of rules that the Parrys instinctively understood but Olivia had never quite figured out?

‘Are you hungry?’ Rowena asked, picking up the bread knife again. ‘I’m making sandwiches.’

Ah, this rule Olivia was familiar with. Refusing food went against the Parry code of conduct. She had discovered this early on in her relationship with Geoffrey, when they first moved to Compton Cross and she was pregnant with Edward. They were often invited to the Rectory for lunch or afternoon tea; occasionally dinner on a Saturday night. Olivia had been laid low with a vague but persistent nausea that lasted well into her sixth month and however much Rowena tried to coax her, she simply had no appetite. This became an unnecessary bone of much contention, Olivia made to feel ungrateful, difficult to please, a generally rather awkward girl. You’re not made to feel like that, you just do, was Geoffrey’s analysis.

An Unsuitable Marriage

An Unsuitable Marriage