- Home

- Colette Dartford

An Unsuitable Marriage Page 2

An Unsuitable Marriage Read online

Page 2

Nevertheless, it prised open a rich seam of innuendo: about Olivia’s lean figure (We didn’t have eating disorders in my day), her domestic failings (Shop-bought is fine if you don’t have time to bake), her general contrariness (You must make me a list of all the things you won’t eat so I don’t forget). Geoffrey insisted she had the habit of taking general and innocuous comments and applying them to herself, hearing criticism that wasn’t there. But irrespective of who was right and who was wrong, Olivia had tired of fighting a battle on two fronts. Easier to go along with whatever was required, which today was to sit round the table, eat sandwiches and play happy families. That Olivia’s stomach churned and she didn’t think she could eat a thing was neither here nor there.

She looked at Geoffrey and made a little gesture with her hand, bringing an imaginary glass to her mouth. Wine at lunchtime would be a rare but much appreciated treat. Alcohol wasn’t allowed on the premises at St Bede’s and on the few occasions she had craved it, she realised it wasn’t the wine she missed, but the ritual of selecting, uncorking, pouring, sipping. It seemed very grown-up, very civilised: a reminder of the life she and Geoffrey used to have. And a small glass of wine might help calm her gnawing apprehension; wash down the unwanted but obligatory sandwich.

Geoffrey produced a bottle of Chablis from the fridge and rummaged around the cutlery draw for a corkscrew – the sort waiters use in good restaurants.

‘Would you like a glass, Mum?’ he asked, deftly opening the bottle.

‘No, thank you,’ she said, ‘but you two go ahead.’

Olivia ignored the tone of permission having been granted and asked if there was anything she could do.

‘All done,’ said Rowena, placing the sandwiches on a large oval plate and ushering Olivia over to the old church pews on either side of the table.

She slid along next to Edward, who had discarded the apple core and was now peeling a banana. He offered her a satsuma but she declined in favour of a deep drink from her glass. Olivia was impatient for the wine to do its job and damp down the panicky feeling that this was all wrong. It wasn’t her life; it couldn’t be.

Edward filled a tumbler from the tap and topped it up with orange squash. Rowena put the platter and a pot of tea on the table, took off her apron and sat down.

‘Well, this is nice,’ she said, passing round white cotton napkins. ‘Have you unpacked, Edward? You know that used to be your father’s room?’

Edward nodded – he wouldn’t speak with food in his mouth. When he finished chewing he said, ‘There are ten of us in my dorm so it’s nice to have a room to myself.’

‘And what about you, Olivia?’ said Rowena. ‘I don’t want you to feel uncomfortable.’

Being told not to feel uncomfortable was itself uncomfortable. Olivia took another hit of wine.

‘I’ll try not to,’ she said, then noticed the way Geoffrey was looking at her. ‘Thank you,’ she added.

Conversation turned to the incident with Freddie Burton, Rowena asking Edward why a child would do such a silly thing; such a dangerous thing. Edward shrugged in an exaggerated way and said Freddie was always doing stupid stuff, that he was a bit of a show-off.

‘Is he a friend of yours?’ Rowena asked.

Edward thought about it for a second. ‘Sometimes,’ was his answer.

Olivia had no wish to compound her uneasiness by being reminded of that dreadful night, so moved the conversation in a different direction.

‘I thought we could take Rollo and Dice for a walk when we’ve finished.’

Rowena turned round so she could see out of the window. ‘It’s raining,’ she said.

‘Still,’ said Olivia, ‘Dalmatians need a lot of exercise.’

‘We always had terriers when Geoffrey was a boy,’ said Rowena, selecting a cheese and pickle sandwich. ‘Very easy little dogs. No trouble at all.’

Olivia heard this as criticism and looked at Geoffrey, willing him to wade in and defend their canine preferences. He pretended not to notice and reached for another sandwich.

‘I don’t mind getting wet,’ said Edward, refreshingly oblivious.

‘Me neither,’ said Olivia, looking straight at Geoffrey.

*

Their walk had been a miserable trudge. Edward wore a pair of Geoffrey’s wellingtons, two sizes too big, because God knows where his were – packed up and put into storage, no doubt. Geoffrey said he would have gone but had important emails to attend to. Olivia hadn’t exactly hidden her disappointment but he pretended not to notice that either. Pretending was one of his skills.

She regretted the wine, how tired and irritable it had made her. Manor Farm came into view from the crest of the hill. Home. The hot sting of tears were another side effect of the wine. She wiped them with a gloved hand before Edward noticed.

When they got back to the Rectory she had excused herself saying she needed to unpack, but what she really needed was to lie down. She had drifted into a three-glasses-of-Chablis sleep – so much for one small glass to settle her nerves – and when Geoffrey had gently roused her at seven for supper, she told him she couldn’t face it. It was a mistake for him to say his mother had gone to a lot of trouble, roasted a chicken, baked an apple and blackberry pie, and couldn’t she just make a bit of an effort? In retrospect, yes, Olivia could have been less vehement in her response, but come on. A bit of an effort? Are you serious? Every day is an effort. What more do you want from me?

So often the thing you’re arguing about isn’t the thing you’re arguing about. It’s a proxy for all the grievances that accumulate throughout a marriage: the things never quite resolved, never quite forgiven. Geoffrey had shaken his head and retreated downstairs, leaving Olivia curled in the foetal position, dry-mouthed but too lethargic to go to the bathroom and fetch a drink of water.

He woke her again when he came to bed – told her it was ten o’clock and she should probably get undressed. It took a few moments to register where she was, that she had missed dinner, that her stomach was empty and rumbling. He took off his clothes, tossed them on to a chair by the dressing table, put on his pyjamas (he never wore pyjamas at home) and went to the bathroom, the creak of floorboards marking his every step.

Olivia produced a dressing gown and toilet bag from her unpacked holdall and shivered as she pulled her jumper over her head. The radiator was stone cold. A draught from the window moved the flimsy curtains to a flutter.

Geoffrey returned and, without a word, slipped under the icy sheet, the itchy woollen blanket, the pink candlewick eiderdown seen only on the beds of those aged seventy and over. Olivia took her turn in the bathroom, quickly brushed her teeth, splashed her face with tepid water and had a much-needed pee. On her way back along the landing she checked on Edward, fast asleep in Geoffrey’s old single bed, his golden curls illuminated by a thin slither of moonlight. She tiptoed over and kissed his forehead like she used to when he was small. Sorry, she whispered, knowing he wouldn’t hear, but needing to say it anyway.

When she got under the covers next to Geoffrey, he didn’t move. She lay on her back, rigid, and stared into the darkness. So much for making the best of things. Day one and she had already screwed up. Guilt pressed down on her. She imagined the scene at supper, Edward asking where Mum was, Geoffrey making some thin excuse. Worst of all, she had played right into Rowena’s hands. How often would she be reminded of the afternoon she drank too much and had to sleep it off instead of joining the family for a roast chicken supper, cooked especially because it was her favourite?

*

The next morning a mug of steaming tea and plate of toast had mysteriously appeared on the bedside table. Olivia propped herself up on the pillows and sipped gratefully from the mug. Geoffrey’s side of the bed was warm but empty. Memories of yesterday eked into her consciousness; ill-fitting pieces of a depressing domestic jigsaw. How could she face Rowena? Or Geoffrey. And what about Edward? Her stomach wafted between hunger and nausea. She started on the toast, hoping it w

ould make her feel better. It galled her to admit it, but Rowena’s bread was delicious: light wholemeal flour with mixed seeds and a good crust. Butter too – none of those bland low-fat spreads. Geoffrey arrived with his own tea and toast and a sheepish look she knew all too well.

‘Feeling better?’ he asked, setting his breakfast down on the dressing table.

‘Feeling stupid and embarrassed,’ she replied.

He came over and perched next to her. ‘Don’t. It’s my fault we’re here. It won’t be for long, I promise.’

Another promise he couldn’t keep. He had no way of knowing how long it would be before they had a home of their own again. The uncertainty was frightening; having no idea what lay ahead. If she thought about it she panicked, so she forced herself not to.

Geoffrey tentatively stroked her hair, as if to gauge her mood. Hard to believe they had spent their first night together in weeks and had barely touched each other. She leaned her head on his hand. So many nights, as she lay alone in her bed at St Bede’s, she had thought about Geoffrey holding her, making love to her, but now that the moment presented itself, she was distracted by the musty smell, the faded floral wallpaper, the heavy mahogany furniture that made the room appear smaller and darker than it was. If she moved his hand away, however gently, it would seem like a rejection so she closed her eyes and imagined they were in their bedroom at Manor Farm, with its huge four-poster and thick cream carpet. No, that didn’t work. All it did was make her miss their home more keenly.

She switched to a different image: her thirtieth birthday at the Four Seasons in Mexico, sun beating down on her tanned bare breasts. OK, that worked better. She relaxed into the sensation of Geoffrey’s lips on her neck, his breath warm on her skin. He slipped his hand under her T-shirt and she arched her back in response. He put his mouth on hers, a vague taste of marmalade on his tongue. She lay back down, eager to feel the weight of his body on hers, and ran her fingers through his tangle of wavy hair. They locked eyes, the anticipation building, when Rowena’s voice brought them bolt upright.

‘Breakfast, Edward. It’s on the table.’

Olivia and Geoffrey froze, like a couple of teenagers caught doing something they shouldn’t. They waited, motionless, as Edward bounded noisily down the stairs, sending Rollo and Dice into a barking duet. Geoffrey took a long breath in through his nose and held it for a moment before he exhaled.

‘That’s that then,’ he said.

*

Olivia wanted to call Lorna but worried about how much could be read into a tone of voice, how the most casual comment, the wrong inflection on a word, a pause where a pause shouldn’t be, might so easily be misinterpreted. Better to send a text – brief and to the point – but Edward beat her to it. After breakfast he had called Josh and arranged to cycle over there. At first he refused Olivia’s offer of a lift, preferring to make his own way on his much prized mountain bike, but when a search of the garage and garden shed proved futile, Geoffrey admitted it might have gone into storage by mistake. Sorry – he would go over and retrieve it later.

Edward wasn’t in the mood to wait so accepted Olivia’s offer after all. She couldn’t say why she didn’t text Lorna to let her know she was coming, except that the same creeping sense of unease stopped her. Not on a conscious level – she wouldn’t allow herself to admit it – but it nagged her, like a tiny ulcer on her tongue. She sent Edward to the village shop for a bag of chocolate eclairs while she dressed and put on a bit of make-up. Geoffrey loitered, as though he wanted to say something but wasn’t sure how. He thought the shift in her friendship with Lorna was down to him. He had said it before and depending on her mood, Olivia either denied it (if she was feeling kind), or agreed with him (if she wasn’t). And yes, it was largely Geoffrey’s fault that Johnny was out of work, that he and Lorna were struggling to pay the bills. How could that not impact on their friendship? But it wasn’t the whole story. There were things Geoffrey and Lorna didn’t know, things Olivia had promised to keep from them.

This morning she was feeling kind. She kissed Geoffrey lightly on the mouth and he pulled her up against him, his hand firm on the small of her back. Edward bounced in with the eclairs, saw them and covered his eyes.

‘Get a room,’ he said with mock disgust.

Geoffrey whispered in Olivia’s ear. ‘I wish.’

*

Johnny and Lorna’s cottage nestled in the middle of a row of five – all identical and picture-perfect until you had to live in one of them. Thatched roofs that needed replacing every twenty years (theirs was overdue), low beams Johnny had to duck, small rooms, big spiders, one bathroom between four, no downstairs toilet. The Grade One listing meant planning for an extension would be denied, but Johnny was adamant he would never move. He had been born in that cottage, in the bedroom he now shared with Lorna. What was it about men and their childhood homes?

Olivia parked on the lane and walked up the garden path with Edward, her heart pattering like rain against glass. Lily opened the front door wearing skinny jeans and an oversized hoodie, straight auburn hair falling like curtains around her pretty face. Such a shame Edward and Lily would never be more than friends. Too familiar – that was the problem. They had known each other all their lives, Lily like the sister Edward never had. Olivia and Lorna had spent many a happy afternoon fantasising about a Parry–Reed marriage: sharing grandchildren, being family as well as friends.

‘That’s mine,’ said Josh, tugging at Lily’s hood, and then to Edward, a matey, ‘All right?’

‘Nice to see you too, Josh,’ said Olivia.

‘Are those for us?’ he asked, relieving her of the bag. He peered inside. ‘Chocolate eclairs. Thanks, Olivia.’

Edward kicked off his trainers and followed the twins into the kitchen but Olivia hung back. If Lorna was home she would have come and said hello. No Benji either – she must be walking him. The children’s chatter spilled out of the kitchen, comforting and familiar. Olivia popped her head round the door.

‘Will Mum be long, do you think?’

Lily turned to her with a mouth full of eclair and shrugged. The boys hadn’t even registered the question. Olivia couldn’t decide if she should wait. That was the problem with secrets. They disrupted the natural flow of things, rendered the simplest decision laden with meaning only you understood.

Perhaps she should come back later, but would Lorna be upset knowing she had been here and left without seeing her? Olivia was wrestling with this when the back door opened and Benji ran in wearing the leather-studded collar Olivia had bought him as a joke a few Christmases ago. A Jack Russell who thought he was a pit bull: snarly, snappy, full of attitude. Lorna had her back to the door, prising off her muddy Hunters with the boot pull. When she turned and saw Olivia, it was a fraction of a second before she smiled.

‘Hello, stranger. When did you get back?’

‘Yesterday. I was going to call but Edward needed a lift.’

It wasn’t clear how Edward needing a lift prevented Olivia from calling, but they moved swiftly past it.

‘Cup of tea?’

The children piled out of the kitchen – something about a wicked new computer game – leaving Olivia and Lorna alone.

‘Love one. I brought cakes.’ Olivia looked in the paper bag. ‘Sorry, there’s only one left. We’ll have to share.’

‘Home-made?’ asked Lorna, filling the kettle.

The tension floated away.

‘Of course,’ said Olivia, mimicking Rowena’s cut-glass accent. ‘One can always find time to bake.’

Lorna chuckled. ‘How is the dowager Parry?’

‘Missing Ronald, I imagine. I promised myself I would be sympathetic but failed abysmally.’

‘Oh?’

‘I lived down to her expectations last night – drank too much wine and slept through supper.’

Lorna made an ‘ouch’ face and poured boiling water into a china teapot. Nothing but loose-leaf tea would do. She considered tea bags the dev

il’s work: expensively flavoured dust. Olivia sat down at the table and cut the eclair in half. The children’s rough and tumble thumped on the heavily beamed ceiling and Olivia realised how much she’d missed this. If she couldn’t be in her own home, this was the next best thing.

Lorna gave the tea a stir and then poured it into two man-sized mugs: ‘World’s Greatest Dad’ on one, ‘Keep Calm and Drink’ on the other. She sat down and took her half of the eclair.

‘Now tell me everything.’

Olivia outlined her six weeks at St Bede’s: the moment she found Freddie Burton (God, that must have been awful. It was all over the news), the fallout (baptism of fire for the new head), how onerous the responsibility of looking after a dozen girls (one is bad enough once the hormones kick in), how hard it was to treat Edward like a pupil and not a son (I can’t imagine). Olivia was about to ask what had been happening with Lorna but that would lead to talk of futile job-hunting, money worries, having Johnny under her feet all day, so she carried on with tales from the Rectory. Olivia versus Rowena; reassuringly familiar territory.

Rowena was the reason Olivia had disliked Lorna before she even got to know her.

They were pregnant at the same time, Olivia recently having moved to Compton Cross, friendless and homesick for Reading, an admission too embarrassing to share with anyone but her mum and dad. She and Lorna had spoken a few times when their paths crossed in the village but severe pre-eclampsia meant Olivia spent the last weeks of her pregnancy in a hospital bed, lonely, frightened, mind-numbingly bored. Edward had to be delivered by Caesarean section at thirty-five weeks, weighing roughly the same as two bags of sugar. Rowena had peered into his hospital cot and announced that Lorna Reed was along the corridor, twins safely delivered, both a healthy six-and-a-half pounds. Oh, and she managed a natural birth. Olivia was left in no doubt whatsoever she had let the side down; failed in some grievous yet unspecified way. Unable to carry a baby to term. Unable to produce a strapping baby. Unable to push said baby out of her vagina. The same vagina that had trapped Geoffrey into an unsuitable marriage. Her vagina, it seemed, had a lot to answer for.

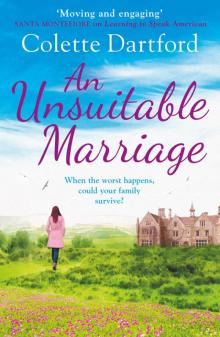

An Unsuitable Marriage

An Unsuitable Marriage